The elsewhere interpretation of quantum mechanics

Real and imagined science in "Wigner and I"

My short story Wigner and I germinated from the idea that asked, “What if conscious observers did have something to do with quantum mechanics?” The speculative, but invented science to make that universe coherent was based on something I’d been toying with since grad school that I named the elsewhere interpretation of quantum mechanics for the story. Part of the reason it came back to mind was reading Susskind’s GR = QM paper on the arXiv. While Susskind is talking about entanglement and computational complexity, pushing the “ER=EPR” hypothesis even further, the elsewhere interpretation is also based on the structure of spacetime.

If we consider two observers1 of some quantum system, the course of that system between the initial state is fundamentally unknowable to either observer in quantum mechanics. And if you try to measure the system in mid-course, it will destroy this path ambiguity and any quantum interference. For example, in a two slit experiment, both slits must be in the elsewhere region for any observing apparatus. If you do measurements up close to the slits, you’ll destroy the interference.

In this toy model, if we integrate over all possible paths for all positions of the observers consistent with the initial and final states along some spacelike slice we arrive at a normal distribution that spreads with time — like a quantum wave packet.

There’s a much more rigorous version of this in Jacobson and Schulman (1984) [pdf] (graphic above on bottom right). That paper looks at the relationship between the Schrodinger equation and the diffusion equation and shows the relativistic version (the Dirac equation) shows different diffusion behavior (i.e. Δx ~ Δt relativistically, but Δx ~ √Δt. non-relativistically with the change-over coming at a scale on the order of the Compton wavelength).

In a sense, we are reifying the many paths of the path integral. However, if you look closely, you can see that these paths involve quite large accelerations. In fact, the theory that’s fully consistent with quantum mechanics that reifies the paths called Bohmian mechanics also implies severe accelerations (graphics above). This paper works out the accelerations of the individual paths in a wavepacket, and for one near the edge (i.e. starts at one of the 1-σ edges) we get an acceleration such that c²/a ~ 1481 fm or about 3.8 Compton wavelengths.

The reason I phrased that acceleration as a distance using the speed of light is because that measure, c²/a, is the distance to the horizon in Rindler coordinates. Now a Rindler horizon isn’t an event horizon like a black hole, but rather separates the regions of space where a signal could or couldn’t reach an accelerating system. Not only is our quantum system elsewhere in terms of the observers, it could be, on the basis of the accelerations given the paths a particle would have to take, on the other side of a horizon. All the observers would really know is that the elsewhere space asymptotically approaches flat Minkowski space at its edge. That could mean we include fluctuating metrics in our path integral.

If all possible spacetimes are allowed in the path integral — and there is some disagreement on whether e.g. wormholes are allowed2 — they could be a source of quantum weirdness. Already, Susskind tells us3 quantum entanglement (Einstein Podolsky Rosen “spooky action at a distance” thought experiment) is potentially related to wormholes (Einsten-Rosen bridge) — that “EPR = ER”. In fact, we can go a bit further if we look at metric fluctuations that introduce area changes.

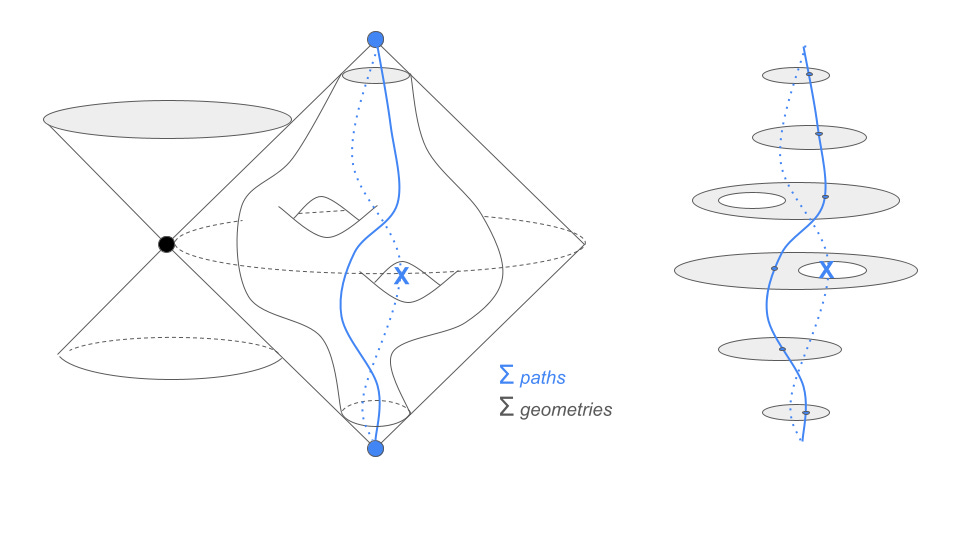

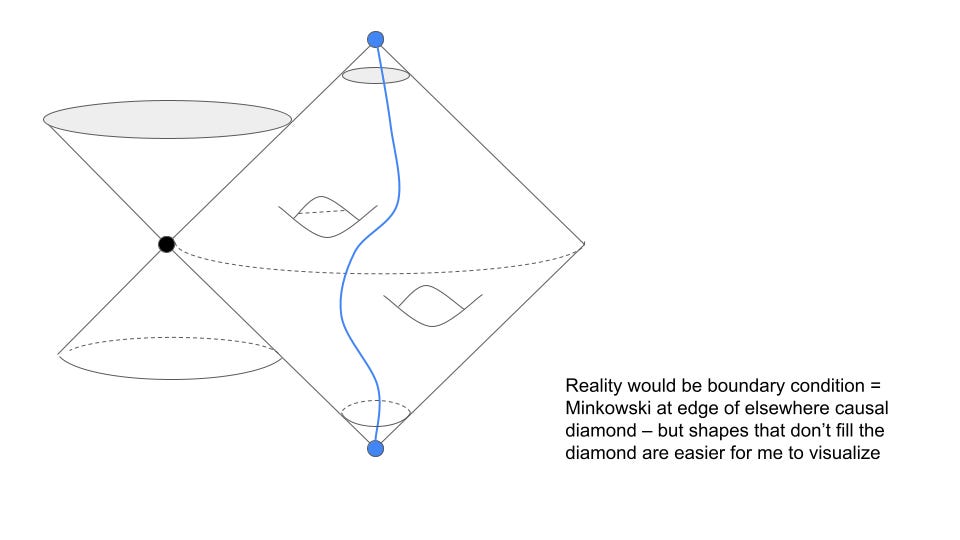

If we look at the “elsewhere causal diamond” (i.e. the intersection of the future light cone from the initial state/past detection with the past light cone of the final state) that nestles up against the observer’s light cone, the many paths can become many paths and many geometries4:

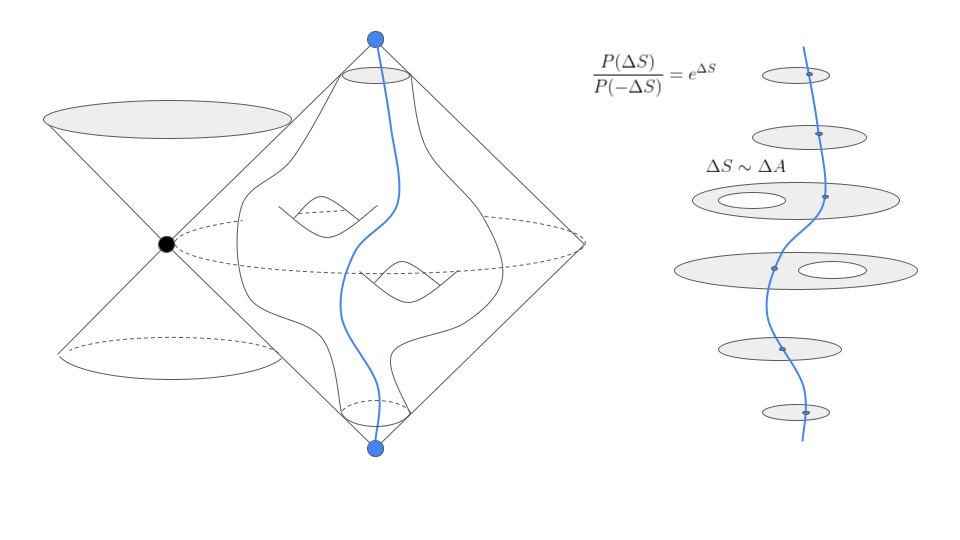

Some geometries will be consistent with certain sets of paths, and some won’t. In fact, the geometries consistent with the apparatus (e.g. the double slit) could potentially guide the particle paths. But there’s an even better back of the envelope plausibility argument here. The fluctuations in boundary area due to geometries with event horizons would be proportional to changes in entropy via the Bekenstein bound — or more to our point, Bousso’s covariant entropy bound (see e.g. here).

The fluctuation theorem relates changes in entropy with probabilities which we can re-arrange to produce a hand-wavy Dirac equation as I show here in my Inner Horizon fake science lecture notes:

Hyperquantum physics lecture notes

Hyperquantum computation limits in a causal volume (P = NP) ‘t Hooft’s holographic principle tells us that all of the information about a region is encoded on a surface bounding that region and the maximum amount of information is given by Bekenstein’s bound

There are of course issues with this — the Wick rotation just introduces the factor of i = √−1 by hand5, it’s an equation for the probability (not the probability amplitude) and there’s no spin). However, it gives us (in a hand-wavy way, for sure) the right scales. The fluctuations in entropy would be on the order of those which makes sense in the Dirac equation.

The larger issue going from these diffusion- and thermodynamics-based approaches is that, sure, you can get noise and fluctuations. But they don’t result in waves or interference unless that factor of i comes in naturally. If, for example, the metric fluctuations had to look a certain way because of the experiment geometry, that could result in the geodesics in the average spacetime in the elsewhere causal diamond looking something like the Bohmian trajectories. However, it seems to just average to flat Minkowski space in the scenarios I can think of — and definitely not higher order modes. The “back of the envelope” argument is there, but not the details.

As a side note — the alternate universe Brian who solves this problem makes a reference to Moiré patterns and coarse-graining; i.e. the limited information going into this causal diamond requires the paths in the integral to contain only a limited amount of information themselves resulting in wave-like behavior. This procedure was totally made up, but was something I’d thought about as a way to get waves from discrete information. Of course, band-limiting the signal information would produce results that look like waves — but that would be begging the question as to band-limit you’d have to be looking at waves already.

Update

In a relatively new paper, there’s a piece of what I was talking about above — quantum superpositions decoherence is connected to Rindler horizons:

As we show, from the Rindler perspective the superposition is decohered by “soft gravitons/photons” that propagate through the Rindler horizon with negligible (Rindler) energy.

I used two observers to make the problem symmetric for the integration that comes later — however, fundamentally the idea of a theory in physics is to be able to describe a measurement that at least two observers agree on.

Wormholes in the path integral potentially help resolve the black hole information paradox and yield the Page curve.

This paper in particular was the one that inspired my short story Wigner and I.

There was a fun paper that introduces the factor of i by taking the absolute value or minus sign out of the metric density for the volume element: √g versus √−g (or more verbosely √|det g|). I mean Kähler manifolds can have a complex metric but that’s because they are complex spaces to begin with. In general, these diffusion- or thermodynamics-related approaches to quantum mechanics are a fun game of “spot where they sneak in i” with Wick rotation being the most common.